- Home

- Monks of New Skete

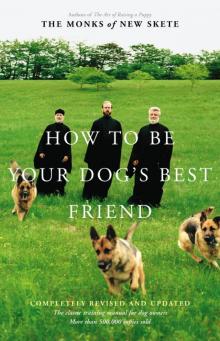

How to Be Your Dog's Best Friend

How to Be Your Dog's Best Friend Read online

The Monks of New Skete

How to Be Your Dog's Best Friend

THE CLASSIC TRAINING MANUAL FOR DOG OWNERS

Completely Revised and Updated

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY

Boston New York London

Copyright © 2002 The Monks of New Skete

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced

in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means,

including information storage and retrieval systems,

without permission in writing from the publisher,

except by a reviewer who may quote

brief passages in a review.

Hachette Book Group, 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

Second Edition

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2438-5

E3-20170707-JV-PC

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Preface to the Second Edition

Acknowledgments

An Introduction to Training

1. Myths, Mutts, and Monks

2. How New Skete Went to the Dogs

3. What Is a Dog?

4. Some Important Terms

5. Selecting a Puppy or Older Dog

6. Researching Canine Roots

7. How to Read a Pedigree

8. Where to Find Training

9. The Concept of Praise in Dog Training

10. Discipline: The Taboo Topic

11. What's Cooking?

12. Grooming Your Dog

13. The Inner Dimension of Training: In the Beginning Is the Relationship

Environments

14. Canine Environments

15. City Life

16. Suburban Life

17. Country Life

18. Outdoor Life

Sensitivity Exercises

19. Your Dog May Be Lonely

20. Where Is Your Dog This Evening?

21. Playing Pavlov

22. Silence and Your Dog

23. Radio Training

24. Massage for Dogs

25. The Round-Robin Recall

26. Keeping Fit for Life

27. Avoid Canine Incarceration!

28. Children and Dogs

Starting Off Right

29. Puppy Training

Standard Obedience Exercises

30. Starting Out

31. Equipment

32. Heeling

33. The Stay

34. The Recall

35. The Down

36. The Down-Stay

37. About Obedience Competition

Problems

38. Understanding Your Dog's Personality: The Problem Explained

39. House Training

40. Chewing, Digging, and Jumping Up

41. Protection Training and Attack Training

42. Alarm Barking

43. Aggressive Behavior, or How to Deal with a Canine Terrorist

44. Behavior In and Out of Cars

45. Social Implications of Training

46. When a Dog Dies: Facing the Death of a Dog

A Parting Word

47. Dogs and the New Consciousness

Discover More Monks of New Skete

Select Reading List

Appendix: AKC Titles and Abbreviations

To our many clients over

the years, whose love for

their dogs has been a constant

source of inspiration for us

Also by the Monks of New Skete

DOG CARE AND TRAINING

The Art of Raising a Puppy

SPIRITUALITY

In the Spirit of Happiness

Learning the value of silence is learning to listen to, instead of screaming at, reality: opening your mind enough to find what the end of someone else's sentence sounds like, or listening to a dog until you discover what is needed instead of imposing yourself in the name of training.

— THOMAS DOBUSH, Monk of New Skete (October 9, 1941–November 7, 1973), in Gleanings, the Journal of New Skete, Winter 1973

I love inseeing. Can you imagine with me how glorious it is to insee, for example, a dog as one passes by. Insee (I don't mean in-spect, which is only a kind of human gymnastic, by means of which one immediately comes out again on the other side of the dog, regarding it merely, so to speak, as a window upon the humanity lying behind it, not that,) — but to let oneself precisely into the dog's very center, the point from which it becomes a dog, the place in it where God, as it were, would have sat down for a moment when the dog was finished, in order to watch it under the influence of its first embarrassments and inspirations and to know that it was good, that nothing was lacking, that it could not have been better made . . . Laugh though you may, dear confidant, if I am to tell you where my all-greatest feeling, my world-feeling, my earthly bliss was to be found, I must confess to you: it was to be found time and again, here and there, in such timeless moments of this divine inseeing.

— RAINER MARIA RILKE, New Poems, Translated by J. B. Leishman

But now ask the beasts and let them teach you,

And the birds of the air and let them tell you,

Or speak to the earth and let it inform you,

And let the fish of the sea recount to you.

Which among these does not know that the hand of God has done this,

In whose palm is the life of every living thing,

And the breath of every human being?

— Job 12:7–10

How to Be Your Dog's Best Friend

Preface to the Second Edition of How to Be Your Dog's Best Friend

Twenty-four years is a long time for any instructional book to go unrevised, but particularly when it applies to a field as dynamic and lively as dog training. Perhaps our biggest reason for delaying such a project until now involved priorities: determining what would be of most help to dog owners and their dogs in the nitty-gritty of their relationships. Experience convinced us that a separate book on puppyhood and a comprehensive set of training videos were of more immediate need, so we applied our energies to those projects.

Still, for a long time now we have wanted to come out with a revised edition of How to Be Your Dog's Best Friend that included the most current ideas about training and dog care. Doing so means being faithful to what we have learned through our experience. In the years following the original edition's publication in 1978, New Skete has been privileged to continue its work with dogs and to share in the growing understanding of all things canine. Many of the insights and intuitions that we first articulated have had the chance to age and become more refined. We have also continued to learn much that is new, benefiting from the work of many talented trainers and animal behaviorists, as well as from the generosity and openness of dog owners and friends who have brought their dogs to the monastery. More significant, our own sense of the mystery that a relationship with a dog brings us into has deepened, too. The result for us has been a more mature and comprehensive understanding and love of training and the human-canine relationship.

We hope that this revised edition will inspire and enable you, our readers, to create a more satisfying relationship with your dog, while at the same time discovering the deeper significance and spiritual value of life with your best friend.

Acknowledgments

All trainers, whether or not they attend schools and clinics themselves, develop a great part of their philosophy and techniques through personal exchanges with others in this field. Many people have helped us through the years, in both our breeding and tra

ining programs, and we would like to make special mention of them here.

From the early days of our work with dogs, several veterinarians were in touch with us on a regular basis through our mutual referrals and their active cooperation with us in handling problem behavior, especially Drs. Joel Edwards and David Wolfe, Shaker Veterinary Hospital, Latham, New York; Drs. Eugene and Jean Ceglowski, Rupert Veterinary Clinic, Rupert, Vermont; Dr. George Glanzberg, North Bennington, Vermont; Dr. Robert Sofarelli, Saratoga Springs, New York; and Dr. Charles Kruger, Seattle, Washington.

A great many professional trainers helped us during their visits to New Skete or in many other ways: Joyce and Don Arner of Westmoreland, New York; Jack Godsil of Galesburg, Illinois; Fred Luby of the United States Customs Office in New York City; William Lejewski of the Baltimore, Maryland, Police Department; Sidney Mihls of Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey; and Diane Moorefield of Atlanta, Georgia.

For supplying invaluable source materials dealing with the whole spectrum of canine-human relations, Dr. Benjamin Hart, University of California at Davis; Evelyn Mancuso of Natick, Massachusetts; and Lynn Levo, C.S.J., of the College of St. Rose at Albany, New York, were most generous, as were the following, whose general assistance and encouragement helped make the original book a reality: Elizabeth Ryder and Marian Finke; Helen and Jack Dougherty; Alice Riggs and Marie Leary; Eva and Ernest Seinfeld; Barbie and Bill Fleischer; Roby and Charles Kaman; Gordon Johnson; Ilse and Tony Govoni; Holly and Paul Carnazza; Roger Donald, Richard McDonough, and Diane Muller of Little, Brown; Jody Milano; the Nuns of New Skete; and our many clients who have entrusted us with the care and training of their dogs.

Since the publication of the original edition of this book, many new friends have been extremely helpful to us in our work. We are especially grateful to Ruth Anderson, Donna Malce, Miriam Barkus, Teresa Van Buren, Dennis McCabe, Cathy Wagoner, and Jeanne Carlson for their friendship and openness in sharing with us insights they have gleaned from working with dogs. Jane Hunter MacMillan has been most generous in supporting our work. Our veterinarian, Tom Wolski, has been a close friend and trusted expert through the years and has had an important role in caring for our dogs. For the new edition of this book, we owe a huge debt of gratitude to John Sann, who came to the rescue with his photographic expertise; to Nicholas Hetko and the Nuns and Companions of New Skete; to our agent, Kate Hartson, whose friendship and professionalism have helped us enormously in our writing endeavors; and to the folks at Little, Brown who have been directly involved with this project, especially Terry Adams, Chika Azuma, and Steve Lamont.

Finally, there is no way that can adequately express our thanks and affection to Helen (Scootie) Sherlock, who throughout these many years of friendship has expended incalculable hours of advice, guidance, and encouragement in every phase of our life and work with dogs here at New Skete.

An Introduction to Training

1

Myths, Mutts, and Monks

It may strike readers as odd to find a book associating monks and dogs. Well, both have been around for a long time. Dogs, we must say, have monks beat by many a century, for according to some legends they even predate humanity.

American Indian myths furnish the most ready examples. For the Kato Indians of California the god Nagaicho, the Great Traveler, took his dog along when he roamed the world creating, sharing his delight in the goodness and variety of his creatures with his little dog. Among the Shawnee of the Algonquin nation who once inhabited the upstate region of New York where our monastery is located, creation was brought about by Kukumthena, the Grandmother, and she, too, is accompanied by a little dog (her grandson tags along as well). Creation in this myth is perpetuated by none other than this mutt, for each day Kukumthena works at weaving a great basket, and when it is completed, the world will end. Fortunately for us, each night the dog unravels her day's work. Those of us who have lost portions of rug, clothing, or furniture to a dog's oral dexterity may never be convinced it could be put to a positive use such as forestalling the end of the world. Still, the myth says a lot about the interrelationship between dogs and humans.

The place of dogs in mythology is by no means limited to North American Indian cultures. It appears to be universal. Greco-Roman literature, for example, features dogs in various roles. Think of Hecate's hounds; the hunting dogs of Diana; and Cerberus, the guardian of Hades. More well known is the tale of Argos, the faithful dog of Odysseus, which is recounted to us by Homer in The Odyssey. It is set in the context of Odysseus' return home after a twenty-year absence — ten years fighting at Troy, and the following ten trying to get back to his wife and son. Over the years, everyone comes to believe that Odysseus died in the war, though his wife, Penelope, continues to refuse the amorous advances of various suitors, always believing that she will see her husband again. The irony of the tale is that when Odysseus finally does arrive back home in the guise of a beggar, neither his wife nor his faithful servant recognize him; the only one who does is his old dog, Argos, who has been waiting faithfully for his master to return.

Then there is Asclepius, god of medicine, who as an infant was saved by being suckled by a bitch. As were, of course, Romulus and Remus, founders of the city of Rome (to stretch a point). Egypt's dogs have been depicted prominently in ancient murals, and many dogs have also come to us intact as mummies. Persian mythology features a dog in the account of creation. The Aztec and Mayan civilizations include one as well. Various tribes of Africa, the Maoris of New Zealand, and other Polynesian cultures, along with the venerable Hindu and Buddhist faiths, have all found some key place for a dog in the legends that have been handed down in both oral and literary traditions.

Stories about dogs abound in Zen literature since many Zen monasteries keep dogs, usually outside the gates. The principle koan "Mu" is used to foster enlightenment and involves a paradoxical question about whether a dog has Buddha-nature or not. In another story, a monk is caught in an ironical game of one-upmanship with a dog:

Once a Zen monk, equipped with his bag for collecting offerings, visited a householder to beg some rice. On the way, the monk was bitten by a dog. The householder asked him this question:

"When a dragon puts even a piece of cloth over himself, it is said that no evil one will ever dare to attack him. You are wrapped up in a monk's robe, and yet you have been hurt by a dog: why is this so?"

It is not mentioned what reply was given by the mendicant monk.

And in another, a continuation of the above story, the unpredictable nature of some dogs is equated with reality itself:

As he nurses his wound, the monk goes to his master and is asked still another question.

Master: "All beings are endowed with the Buddha-nature: is this really so?"

Monk: "Yes, it is."

Then pointing to a picture of a dog on the wall, the wise old man asked: "Is this, too, endowed with the Buddha-nature?"

The monk did not know what to say.

Whereupon the answer was given for him. "Look out, the dog bites!"*

We should not shortchange the Judeo-Christian inheritance that many of us share. But in fact the Bible, for reasons we cannot examine here, has only an occasional mention of dogs — for example, "Lazarus' wounds being licked by dogs" or "even the housedogs get the crumbs" in the Gospels. However, the dog reappears in other religious literature, sometimes as a symbol of faithfulness, sometimes as a little detail that lends a warm and human touch to the story of a saint's life. Perhaps the most vivid example of this penetration of folk legend into church tradition is the story of Saint Christopher. Many people will be startled by the way he is pictured in Eastern Christian art. The Menaion, or Book of Calendar Feasts, includes a brief account of each saint's life. We learn from this book that Christopher was a descendant of the Cynocephali, a legendary race of giants with human bodies and canine heads. He is pictured thus in icons. He has the head of a dog but otherwise resembles the conventional image of a martyr, down to the cross in his hand. He was

miraculously converted and baptized, and given the name Christopher, which means "Christ-bearer."

When depicted in iconography, Saint Christopher has the head of a dog. Later he is turned into a handsome brute.

Many saints in the Orthodox tradition are called God-bearer or Christ-bearer, a salutary title meaning these saints carry divine qualities within and manifest them in their daily lives. In the West the title was taken literally with regard to Christopher, and the legend subsequently developed in which the man (an unattractive giant still) carried the Christ Child across a flooded stream and was transformed into a handsome brute instead. In Middle Eastern tradition he journeyed to Syria to attempt to make an evil pagan king, Dagon by name, see the light. The king was not impressed, even by so formidable a messenger as a dog-faced man. Christopher was imprisoned instead, and in the midst of his martyrdom (he was given the first hot seat on record: Dagon ordered him to be chained to an iron throne and then had a fire built under it — so hot, it is recorded, that both chain and chair melted) he was transformed and received the face of a man.

There is a story, perhaps still told in Romania, where it is thought to have originated, that gives a charming account of how the dog itself was created.*It seems that Saint Peter was taking a stroll in heaven with God when a dog came up. "What's that?" said Saint Peter. God told him it was a dog, adding, "Do you want to know why I made him?" Naturally Peter was interested. "Well, you know how much trouble my brother, the Devil, has caused me . . . how he made me drive Adam and Eve out of Paradise. The poor things nearly starved, so I gave them sheep for meat and warm wool to clothe them. And now that fellow is making a wolf to harass and destroy the sheep! So I have made a dog. He knows how to drive the wolf away. He will guard the flocks. He will guard the possessions of man."

How to Be Your Dog's Best Friend

How to Be Your Dog's Best Friend